Consider a semi-truck weighing 80,000 pounds that is traveling at 70 miles per hour on a highway. Now, suppose that the driver at the wheel has not slept for the last 20 hours. To avoid this risky situation, the Department of Transportation (DOT) implements hours-of-service (HOS) regulations. This is a comprehensive set of federal safety regulations and measures designed to help prevent exhausted drivers from being on the road.

These rules, administered by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA), define the allowable working hours of commercial drivers, after which they are legally required to take a break. HOS is the clock that determines your profession, whether you are a long-haul trucker or a fleet manager.

It caters to both the supply chain demands, which are high pressure, and the biological requirement of sleep, so that all miles traveled are safe ones. Since the driving limit is 11 hours and the working day is 14 hours, it is essential to understand how these two periods align to ensure consistency and enhance roadway safety for all users.

How to Know Your Commercial Motor Vehicle (CMV) Status in California

The most critical factor in determining the compliance of a commercial motor vehicle (CMV) in California is the evaluation of the necessity of the freight movement, rather than merely checking the route the driver traversed. This fundamental difference determines the applicability of the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Regulations (FMCSRs) or California Title 13 CCRs, primarily based on the shipper's fixed and continuing intent regarding the shipment's destination.

A movement qualifies as interstate commerce, mandating adherence to federal rules, whenever the vehicle or its load physically crosses a state or international boundary. Furthermore, a shipment that originates in a single state or country and is ultimately destined for another state or country is still considered interstate, even if the driver only crosses a portion of the state. For example, a shipment where a driver is transporting a container whose bill of lading displays an international origin, although the destination is a warehouse in Fresno.

Since federal laws typically supersede state authority, any declaration of a trip as interstate commerce automatically triggers the compulsory enforcement of Federal Hours of Service (HOS) regulations. On the other hand, drivers are only eligible for the less restrictive Title 13 CCR HOS rules under the limited circumstance that the load originated, ended, and was always bound by a location that is entirely within the borders of the state.

This strong boundary has the effect of ensuring uniformity in the implementation of safety standards. However, there is one significant exception to the rule in the case of carriers transporting placarded quantities of hazardous materials. Whether the transportation is intrastate or interstate, all operations involving the transportation of placarded amounts of hazardous materials must comply with the Federal HOS rules.

Being aware of the specific differences in these HOS regulations, it is possible to highlight the practical significance of ensuring compliance with the correct standards. In the case of property-carrying drivers, California intrastate regulations permit a maximum of 12 hours of driving time on a 16-hour duty period, as opposed to 11 hours of driving time on a 14-hour duty period, which is the federal standard.

This difference extends up to the weekly limit, whereby California has 80 hours within eight consecutive days, whereas the federal limit is 70 hours. Moreover, California's intrastate short-haul exemption is more restrictive than the federal version, with drivers having a 100-mile radius and a 12-hour shift restriction compared to the federal 150 air-mile and 14-hour limits.

Carriers formalize their status through mandatory registration identifiers. Interstate Commerce operations should also receive a USDOT number to be supervised by the federal government as the unique identifier that can be used to track the safety performance of a carrier throughout the U.S. Thereafter, the commercial motor vehicles (CMV) that conduct business in California and even the interstate carriers carrying out local collections and deliveries of goods will also need to obtain a CA Number at the California Highway Patrol.

Therefore, the USDOT Number and Federal HOS regulations apply to most of the commercial activity, depending on the origin or destination of the freight. In contrast, the CA number and California HOS regulations apply only to intrastate operations.

Hours of Service Limits: Federal vs. California (Intrastate)

The situation between federal and California intrastate hours-of-service regulations confounds commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers, primarily due to the differences between the two.

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) sets the national standard, which states that drivers must not drive more than 11 hours following 10 consecutive hours off duty in a 14-hour working shift. More importantly, the drivers of both federal and California intrastate commerce are required to take 10 consecutive hours off duty, which in turn establishes a minimum standard for fatigue prevention within the industry.

California, however, is more flexible in its operations, favoring carriers that operate entirely within its borders. Although the mandatory 10-hour off-duty time is not reduced, the intrastate rules permit drivers to increase the daily driving limit to 12 hours and extend the maximum working time to 16 consecutive hours.

This extra hour of trucking and two hours of scheduled time enable the California-based trucking companies and their drivers to traverse the state and the congested cities. They do so with reduced strain, as they can suddenly halt the work, which is a significant benefit of local distribution and long hauls that do not cross state borders.

This flexibility creates compliance risks for drivers operating near state borders, as well as for those working along state boundaries. The only difference between HOS compliance and noncompliance is based on the type of commerce. The 12-hour CA rule will govern the driver with intrastate operations.

However, the moment the driver enters another state, or the freight transported by the driver is related to interstate movement, the trip immediately becomes subject to interstate commerce, and the strict Federal 11-hour limit applies. A driver who reaches hour 11 and proceeds to the state border, being perfectly legal under California law, instantly violates federal law once in another state.

As a result, drivers must estimate their driving time in accordance with the most restrictive rule, even if they stand even the slightest chance of crossing one state line into another. Assume that a motorist is travelling at 11 hours and 30 minutes, driving between California and Nevada. The driver, who was compliant a minute ago, is now 30 minutes above the FMCSA 11-hour maximum.

This direct breach of federal HOS regulations attracts heavy punishment, including hefty fines and adverse effects on the safety history of the driver and carrier. This is the reason the Federal 11-hour rule, as a safety cutoff on any occasion when there is a chance of interstate freight operations, is absolutely imperative.

Comparative Analysis of Truck Driver Duty Window (Federal (FMCSA) and California (Intrastate))

Below is an overview of the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) regulations and the specific intrastate regulations applicable in California.

-

Federal (FMCSA) 14-Hour Duty Window

The Federal 14-hour rule, which is one of the pillars of Hours-of-Service (HOS) regulations, is a time constraint under which a driver carrying property may be employed after taking a necessary break. This stage is commonly referred to as a non-extendable 14-hour duty window.

The timekeeping of the clock commences once the driver has embarked on any on-duty activity after 10 straight hours without duty. Every activity, including driving, non-driving activities, and all work activities, must occur within this set of 14 hours. Under this window, a driver can only drive for up to 11 hours.

A mandatory 30-minute break must be taken after eight cumulative hours of driving time, which must interrupt the driving period. However, it does not stop the 14-hour clock. The driver will need one continuous and uninterrupted 10-hour off-duty period to reopen the duty window.

The federal 14-hour duty clock is a non-pausable clock that works 24 hours. When it begins, it continues until it expires without regard to whether there are short off-duty breaks like lunch (unless a specific exception, like the split sleeper berth rule, is used).

-

California (CA Intrastate) Duty Window

Intrastate HOS regulations in California are limited to those drivers who are entirely within the state and are not engaged in interstate business. These state regulations are more flexible than the federal limits.

California intrastate drivers are entitled to a 16-hour duty window, which is two hours longer than the federal limit of 14 hours. In this window, the maximum driving limit is 12 hours, which is an hour more than the federal 11-hour limit. Moreover, they may not exceed 15 hours of on-duty time; however, after this time, the drivers may still be required to drive, despite having 16 hours of duty completion time, which began at the start of the shift. The requirement applies to the reset: 10 hours off duty in a row, as per the federal law.

This 16-hour allowance is beneficial to California intrastate drivers who face heavy city traffic or must endure lengthy loading or unloading schedules at ports and warehouses. It provides them with extra time to work within the law.

-

"On-Duty Time"

The exact meaning of "on-duty time” is crucial, as a minute can significantly impact the 14-hour or 16-hour duty window provided by federal and California laws. “On-duty time” refers to the time a driver spends working or when they are required to be ready to work. This includes:

- Driving time (operating the commercial motor vehicle)

- Conducting pre-trip and post-trip inspections, servicing, repairing, or refueling the vehicle (inspections)

- The loading, unloading, supervision, or care of the cargo (loading or unloading)

- The completion of the necessary documentation, like accident reports or ELD entries (paperwork)

- Waiting to be loaded, or waiting till the vehicle or load is serviced at a terminal or shipper (waiting time)

- Riding in a CMV as a co-driver, except in the sleeper berth (co-driver travel)

On-duty time does not include legitimate off-duty periods, like meals, sleep, personal errands, or time spent resting in a sleeper berth.

-

Techniques to Extend or Interrupt the Federal 14-Hour Clock

The Federal 14-hour clock is rigid. However, two provisions would enable drivers to have greater flexibility in their duty windows.

The 16-Hour Short-Haul Exception (FMCSA)

This exemption permits qualified short-haul drivers to operate for 16 hours, rather than 14 hours, every seven consecutive days (or after a 34-hour break) without violating the 14-hour limit. Under this exception, the driver should be released from duty and return to their usual place of work, reporting within 16 hours. More importantly, the driver is not allowed to work more than 11 hours in the extended 16-hour period. This exception is permissible only after every 7 days.

Split Sleeper Berth Provision (FMCSA)

This is the primary method for suspending the 14-hour clock. It allows a driver to divide the necessary 10-hour off-duty period into two parts, thereby pausing the 14-hour clock during the breaks. The split that is needed should be:

- A more extended break of at least seven full hours in the sleeper berth

- A shorter break of at least two consecutive hours (can be off duty or in a sleeper berth)

Neither of these periods affects the 14-hour duty window, and they suspend the clock during the breaks. The amount of time of the two breaks taken should still amount to 10 hours to meet the off-duty requirement. The driver should then determine the 11 hours of available driving time and the 14 hours of available duty window remaining after the first break.

Weekly Limits (Cycle Rules)

In addition to the daily duty window, both federal and California regulations have long-term cumulative duty limits that restrict the total cumulative on-duty time over a specified number of days. These restrictions are known as cycle rules or recap hours.

In accordance with federal regulations (FMCSA), drivers are required to comply with either of two cycles. This includes 60 hours of on-duty time within seven consecutive days or 70 hours of on-duty time within eight consecutive days. The decision is usually based on whether the carrier operates on a 7- or 8-day schedule.

Intrastate regulations in California offer a longer cycle limit, which allows drivers to have up to 80 hours of on-duty time in any eight consecutive days. This disparity, with an additional 10 hours beyond the federal 8-day cycle, further highlights the flexibility that California offers its intrastate drivers.

Under both federal and California regulations, the method for redeeming the number of hours in accumulated cycles to zero is the same: the driver must take a 34-hour restart period in one sitting. The accumulation caps (70 hours in the federal and 80 hours in California) vary considerably, which impacts scheduling over the long term and management of driver hours.

The 30-Minute Break

Under FMCSA regulations, property-carrying drivers must take a 30-minute break after eight cumulative hours of driving. This rest period should be between the driving hours, and then the driver will not be in a position to operate the vehicle in accordance with the law. By comparison, California intrastate regulations for CMV drivers do not have a specific hours-of-service requirement for a 30-minute rest following eight cumulative hours of driving.

In the case of employee drivers, California labor laws regarding meal and rest breaks will still apply. Although the absence of an HOS-privileged 30-minute meal break does not constitute a separate violation of state trucking regulations, a missed or untimely meal break would still constitute a violation of labor law.

Federal and CA Driving Extensions

The federal and California regulations provide relief to drivers who are faced with unforeseen holdups due to unpredictable weather conditions or other road hazards, which prevent them from proceeding with their route within the standard working time. This is referred to as the adverse driving conditions exception.

Federal (FMCSA) regulations stipulate that when a driver is faced with challenging driving conditions (snow, ice, fog, or abnormal traffic congestion previously unknown during the time of dispatch), he/she may extend his/her maximum 11-hour driving time as well as the 14-hour duty time by 2 hours. This will enable a driver to extend driving and duty limits by up to two hours to reach a safe stopping location.

California's emergency condition offers a comparable 2-hour exemption. Enforcement, however, is more lenient. The condition is supposed to be a genuine and unforeseen emergency that could not have been foreseen. Typical occurrences, including predictable traffic during rush hours or average weather conditions of a given season, are not considered to be covered under this exception in California. Both jurisdictions would require strict proof and logging to warrant the application of this exception.

Electronic Logging Devices (ELDS) in California

California has done much to harmonize its intrastate compliance standards with those of the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration. It has achieved this by implementing the Federal ELD standard for intrastate commercial drivers, which is effective for intrastate operations as of January 1, 2024. This substitution requires that drivers who previously carried paper records of duty status (RODS) must now use an approved electronic logging device (ELD).

This requirement has two serious exemptions for local drivers:

- Vehicle age exemption — CMVs manufactured before model year 2000 are also exempt, as the older engines they have usually do not provide the electronic control module necessary to connect with an ELD.

- Exception of short-haul record of duty status (RODS) (100 air-miles) — This is the most widespread exemption of the local California drivers to the use of ELD. The exemption for intrastate drivers who work within a range of 100 air miles of their point of origin, or home, and return within a span of 12 hours is a waiver of maintaining any RODS. Such drivers are allowed to use timecards instead of logs, and as such, an ELD is unnecessary.

Although the state of California also allows the application of the Federal 150-mile radius exemption, the exemption is limited, as it only exempts the driver from using an ELD. The driver will still be required to keep track of their hours. When a driver works beyond a 100-mile radius but less than 150 miles, they are generally expected to record their hours in paper logbooks or logging software, rather than using an ELD.

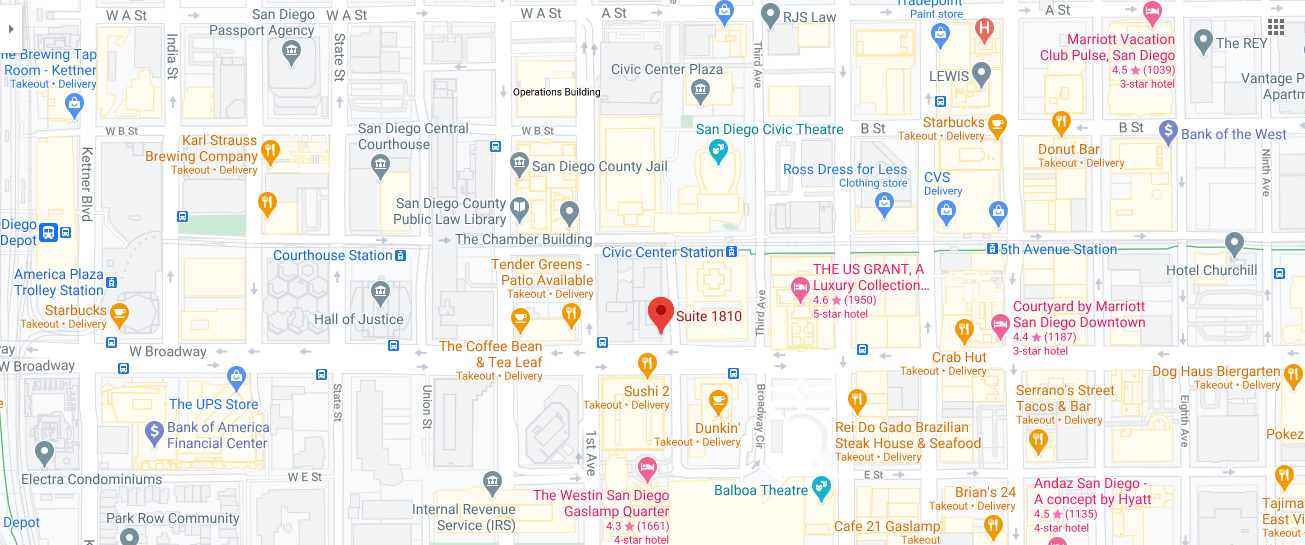

Find a Personal Injury Attorney Near Me

The hours of service regulations in DOT are the barrier between a normal highway and a devastating road accident. These measures will eliminate driver fatigue, which leads to thousands of accidents that can be avoided annually by requiring adequate rest. However, in situations where profit is more crucial than safety, rules are flouted, and innocent individuals suffer.

If you or a loved one has been injured in a truck accident, proving an HOS violation is key to your recovery. Truck Accident Injury Attorney Law Firm deals with holding careless trucking firms liable. We explore logbooks and ELD records to win the highest possible compensation you are entitled to. Contact our California team today at 888-511-3139 for a free consultation, and let us fight for your justice.